In an effort to generate discussion about the regulation of online insurance sales and processes in Canada, the Canadian Council of Insurance Regulators has published a paper, seeking commentary from stakeholders.The issues paper, entitled Electronic Commerce in Insurance Products, was published in January, with a follow-up letter to stakeholders issued the following month, calling on the industry to review the council’s initial perceptions, goals and presumptions.

Peter Goldthorpe, director of marketplace regulation issues at the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (CLHIA), says the fact that the document is an issues paper, rather than a consultation paper, is significant. “It signals an openness to look at the issues at a fairly fundamental level. Anyone who has an interest in how these products are sold has an interest in looking at this paper and responding to it because this will shape the direction that further policy development takes,” he says. “As you get further down the road and (the CCIR) starts issuing formal consultation papers, there’s more investment in them and it becomes more difficult to introduce change.”

His colleague, Frank Zinatelli, CLHIA vice president and general counsel, agrees, pointing out that when any party is developing systems, they frequently come back to their source documents to reference. “In a sense, this could be the source document in this area for a little while.”

To facilitate discussion about future regulation development, the paper outlines in a fair amount of detail, the rules and regulations already in place in Europe and the United Kingdom. It also acknowledges and outlines the existing laws, rules and voluntary codes already in place to govern electronic commerce in Canada, but points out that none specifically apply to financial product distribution. “Much of the insurance legislation currently in place in Canada was developed long before electronic transactions were contemplated,” say the report’s authors.

Because of this, existing legislation dictates that certain transactions must be performed by mail. Such circumstances, they say, have been cited by industry participants as factors which inhibit the growth of electronic commerce for insurance products.

Beneficiary designations

Although it does not come out and say as much or take a position either way, the CCIR’s focus on beneficiary designations and the fact that these can’t be made in electronic form, suggests that rules requiring people to complete such tasks on paper and often long after the sale is made, could be inhibiting consumer protection efforts as well.

In short, the council of regulators says it wants stakeholders’ input into how it should best achieve certain consumer protection goals in an electronic commerce context and how certain rules or guidelines are already being applied in practice today.

The council is looking for several different kinds of feedback, including whether the issues identified are indeed significant and whether these have the potential to negatively affect consumers, whether all significant issues have been identified, how risks should be managed, whether the proposed remedies to identified risks are suitable and whether the description of the topic is factually accurate.

Mr. Goldthorpe draws attention to this last item, pointing out that there is usually a lot more happening on the ground than might be considered in a paper or in various regulator offices. “My experience is there’s usually more going on out in the field than people are aware of at any point in time,” he says. “We’ll be getting input from members.”

Another area he points to are the discussion points about privacy. “They’re pretty bare bones. It’s just one example of a descriptive area that I expect will be expanded on considerably. The industry has pretty robust practices in place.” Mr. Zinatelli says the CLHIA has a privacy code of conduct that was first drafted and introduced back in 1981.

As for the paper’s initial focus on property and casualty distribution, Mr. Zinatelli says it will be the job of member companies and associations to draw out certain points to make sure regulators understand if certain points are not applicable to both sides of the industry. “Our job will be to distinguish where there should be a difference and draw that to their attention,” he says. “The regulators, they know this stuff. When we point out that something doesn’t apply, they recognize it very easily.”

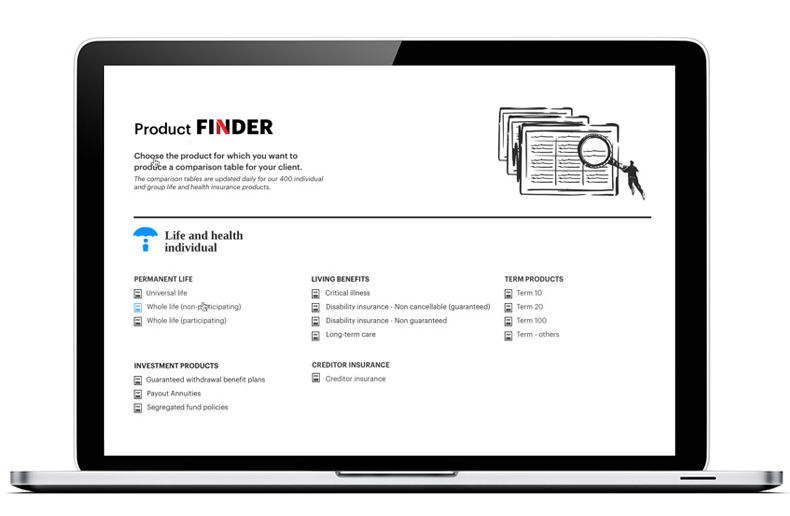

As part of its initial review, the CCIR’s Electronic Commerce Committee (ECC), led by the Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF), compiled a list of websites operated by insurance providers.

“Today, most industry players use the Internet in one way or another as part of their distribution process,” they write. Existing websites, they say, are primarily used today to provide information and advice, quotes and to conclude sales.

Happily for life agents, the paper also recognizes the role intermediaries play in the distribution of insurance products. It points out that a “substantial information imbalance” exists between consumers and insurers, a gap which has traditionally been narrowed or bridged by intermediaries. “With the Internet,” they say, this “personalized advice may be absent, or greatly weakened,” which can lead to several undesirable situations, including the risk clients may be holding invalid contracts or inappropriate coverage.

At present, rules which guide and govern electronic commerce in Canada are a patchwork of voluntary and legislated schemes that apply to electronic transactions generally. For background, the paper discusses these and the efforts which lead to the development and implementation of each.

Canada’s Uniform Electronic Commerce Act (UECA), for example, is based on a 1996 United Nations Commission on International Trade Law Model Law on Electronic Commerce – a model which was intended to be an internationally acceptable, non-exhaustive set of standards designed to enable commerce. The Canadian act provides model rules for the legal recognition of information in electronic form. At present, in some cases, this legal recognition is trumped by more specific insurance legislation – the requirement that consumers make beneficiary designations on paper is one example.

Other regulations and codes outlined in the paper include the 2004 Canadian Code of Practice for Consumer Protection in Electronic Commerce, based on a 1999 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) consumer protection guidelines, and the use of electronic signatures as outlined under Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA).

United Kingdom

In comparison, the United Kingdom and the European Union have both established regulatory benchmarks to govern online insurance distribution. These dictate the information requirements that must accompany insurance sales, including key information about the insurer, where it is located and how the insurer is governed or regulated. Insurers must also provide detailed information about the insurance contract being purchased and redress information for consumers with a complaint.

Using these as a basis, the CCIR lists a number of consumer protection outcomes of its own and begins to develop commentary about the activity and disclosure it will likely require from Canadian insurers in the future.

“Given the importance of exclusions and limitations, highlighting this information or separating it from other important information,” for example, is one approach discussed. “Ensuring the information is written in clear, simple language comparable to the information one would expect a consumer would receive if they were speaking directly to a licensed intermediary,” is another principle that will likely guide the development of future sales material.

Insurers’ websites

The CCIR also proposes to govern the content of an insurer’s website: “The Internet contains a wealth of information and advertising designed to attract and influence consumers. The ECC is of the view that the pages on a provider’s website relating to an application are not an appropriate environment for guiding consumer’s choices.” It goes on to ask if this should be addressed by prohibiting companies from posting advertising on certain pages.

With consumer protection in mind, the paper also discusses the delivery of terms and conditions, the consequences and responsibility insurers have if transactions are not completed successfully and, again, the security of personal information.

As discussed before too, the paper also pays a notable amount of attention to current rules which require that clients make beneficiary designations on paper.

Of concern is the fact that beneficiary designations made electronically today are generally invalid because the current laws do not recognize this as a designation made “in writing.” No insurer currently accepts designations made electronically. Not only can this result in delayed payment to beneficiaries, the proceeds left to the deceased’s estate are thus rendered taxable and vulnerable to creditor claims. In general, clients who do not sign and return the paper forms sent to them are regarded as not having designated any beneficiary, even if they identified one during their Internet application.

Worse, they say, “in a fairly shocking result, two large direct sellers of life insurance recently conducted internal surveys that found 65 percent and 63 per cent of individuals who bought life insurance policies do not have beneficiary forms on file.” One of these insurers added that many of the forms it does receive are not processed “either because consumers did not use the paper form provided, they did not complete the form properly or they tried to provide beneficiary information by fax or phone.”

The complete issues paper can be downloaded from the CCIR website, www.ccir-ccrra.org. The council asks that all interested parties review and comment on the paper by April 27, 2012.