Over the last couple of years, an increasing number of Glen Dodd’s clients began to discreetly ask the 71-year-old financial advisor when he was going to retire.

It didn’t take long for him to get the hint.

“I truly do love what I do,” said the Vancouver-based advisor. “But I could see there was a time when I was going to have to think about retiring and bringing in a partner into the business that I would be comfortable handing the practice over to down the road.”

So, a couple of years ago, Dodd, whose managing general agency is PPI Financial Group, embarked on a journey to find his successor – and to his delight he discovered the right choice for himself.

Dodd is one of what the industry says is an embarrassingly small number of aging financial advisors who has actually thought about putting together a succession plan, one that the advisor could either sell outright or bring in a younger advisor with similar beliefs to take over in the future.

Few have formalized plans

In fact, a recent survey by Investment Planning Counsel (IPC) and Environics Research Group suggests that 69 per cent of the advisors surveyed said they were nearing retirement or have started to cobble together a succession plan. But only 11 per cent actually have a formalized plan and a whopping 75 per cent said they have only a rough idea for a plan or no plan at all.

Some MGAs – like IPC and PPI for example – have stepped in and are picking up the gauntlet, helping their financial advisors find the best retirement solution.

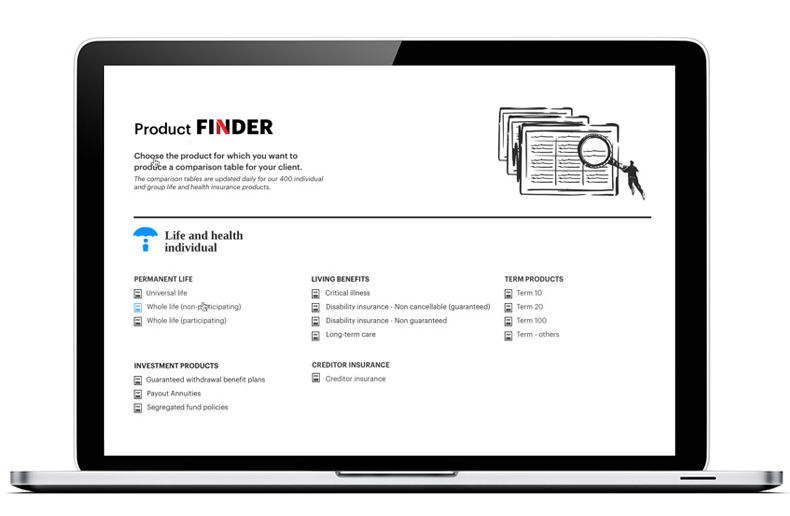

PPI, for one, has partnered with transition management firm FindBob, which takes a page from successful online dating strategies and lets advisors match themselves up with other advisors who are also looking to team up, sell, or buy a book of business.

“We know that many advisors don’t have a written and actionable transition or continuity plan – that risks exposing their business to leaving huge revenue opportunities on the table, certainly in the event of death and disability but even in retirement,” says Cathy Hiscott, senior vice president, Innovation & Strategy at PPI.

With FindBob, advisors can put as much information as they want into the online service and it remains completely anonymous until the advisor wants to engage. While the system is available to the Canadian financial services industry, Hiscott says PPI has personalized the system so it meets the needs of its advisors.

PPI also has its Knowledge Program, which provides sessions on topics such as transition objectives and key considerations like valuations and financing options, as well as case studies to help advisors find the win-win in a transaction. A PPI team can walk the advisor through questions and how to fill in the blanks on FindBob, says Hiscott.

PPI does not typically buy a book of business from its advisors or get involved in the mediation process. “We don’t encourage this. We would much prefer with our 15 offices across Canada, to educate our advisors and help them utilize our local sales vice presidents to guide advisors and help them make the best decision for their business.”

Grooming a junior successor

Over at IPC, there are a number of options open for its advisors, says John Novachis, the MGA’s executive vice president. He says IPC advisors can groom a junior successor, sell to a peer or sell to IPC, the latest of which has been in place for the last three years.

Novachis suggests to advisors that even if they want to work past 65 or 70, they should put the planning in place and give themselves some time to think about their options, so that when the time comes for retirement they will know what they want to do and may even have a strong successor ready to step in. This will help alleviate one of an advisor’s biggest fears of who will look after their clients with the same capabilities and commitments that they had to the business.

When it comes to the third option, IPC will consider being the buyer of a certain size book of business, select a successor and then have that successor work within the auspices of IPC. (IPC says it is the only MGA offering this option on both the insurance and investment management side.)

Novachis acknowledges there are not a lot of young people coming into the business and those who do may find it very difficult to build a business from scratch. “If you’re a capable young advisor wanting to have success in this business unless you’re capitalized to do it, it’s hard to break in.”

Valuation is another difficulty, he adds. An independent advisor could have a business worth, say, $3 million. But most young people don’t have that kind of money.

Novachis says the option of selling to IPC is unique in that the selling advisor is dealing with an institution on the purchase, the institution has the financial capability to pay the advisor and the knowledge of how to run the business. IPC then hires the successor advisor as an employee who would work directly for IPC.

Client retention

IPC typically puts out an upfront payment of 50-60 per cent of the purchase price, pays another 20 per cent after a year and then pays the remainder after a retention test. He says IPC has a 97 per cent client retention rate after two years.

The MGA runs virtual seminars with expert speakers and advisors looking to buy and sell. One recent seminar included 400 advisors, 250 of whom were external advisors.

When it comes to life insurance, all of these issues are problems the life industry brought on itself, says advisor coach Jim Ruta. In the 1990s, says Ruta, advisors received deferred commission income (DCI) and then when they retired the company took back their business and gave advisors their pensions. “So, the issue wasn’t even an issue.”

At the same time, life insurers were constantly recruiting people who would take up the advisors’ business.

But that was then. Where there used to be a career-oriented system with 53 or so different organizations building their companies – plus recruiting – now there are only a handful.

As well, the insurers, especially those that demutualized, made advisors independent, owning their own books of business.

On top of all that, people everywhere are working longer and that includes life insurance advisors, even though much of the income comes in the first couple of years after a life sale.

“There’s not a lot of money to sell a life insurance book and often they’re almost given away along with segregated funds where you do have a recurring stream of income that you can value,” says Ruta.

Emergency succession planning

Even advisors who haven’t decided on a succession plan should think of pulling together a plan of emergency succession. Under this scenario, two advisors agree that if one gets ill for say, three months, the other advisor will look after their business for that time. After that, a decision must be made as to whether this will now turn full-time. Each advisor would get the first right of refusal on their book of business if the other advisor wants to buy it.

But Ruta says the longer term and best solution is for a middle-age advisor to bring in a younger associate as part of a growth strategy, one who can remain when the older advisor decides to retire.

That’s exactly what Dodd did when he embarked on FindBob with PPI. Dodd was given the opportunity to interview the advisors he felt would best suit his needs and those of his clients. The advisor brought the number down to a short list and selected Mike Savoy, 43, as his successor.

“I owe it to my clients to make sure they are good hands when I’m ready to retire. I think more advisors in my age group should be thinking and planning their exit strategy and I don’t think enough of us are.” - Glen Dodd

Savoy’s office is in nearby Burnaby, B.C. where Dodd says he will be working soon, even though the two will be operating separately for the time being.

The pair has worked out an agreement on how Dodd will be compensated for his book of business in a deal that will officially take place Jan. 1, 2025 when Dodd will be almost 75. He’s structured the buyout over a seven-year-period; financially it works out well for the two of them.

“My observation is that there are a lot of us getting on in age and I don’t think a lot of us have spent the time necessary to go through the process I have been going through,” says Dodd.

“My clients are loyal and I owe it to my clients to make sure they are good hands when I’m ready to retire. I think more advisors in my age group should be thinking and planning their exit strategy and I don’t think enough of us are.”